Written by Victoria Miller, a junior from Boston College majoring in International Studies apart of the Spring ‘23 cohort and interning for The European Center for the Study of War and Peace

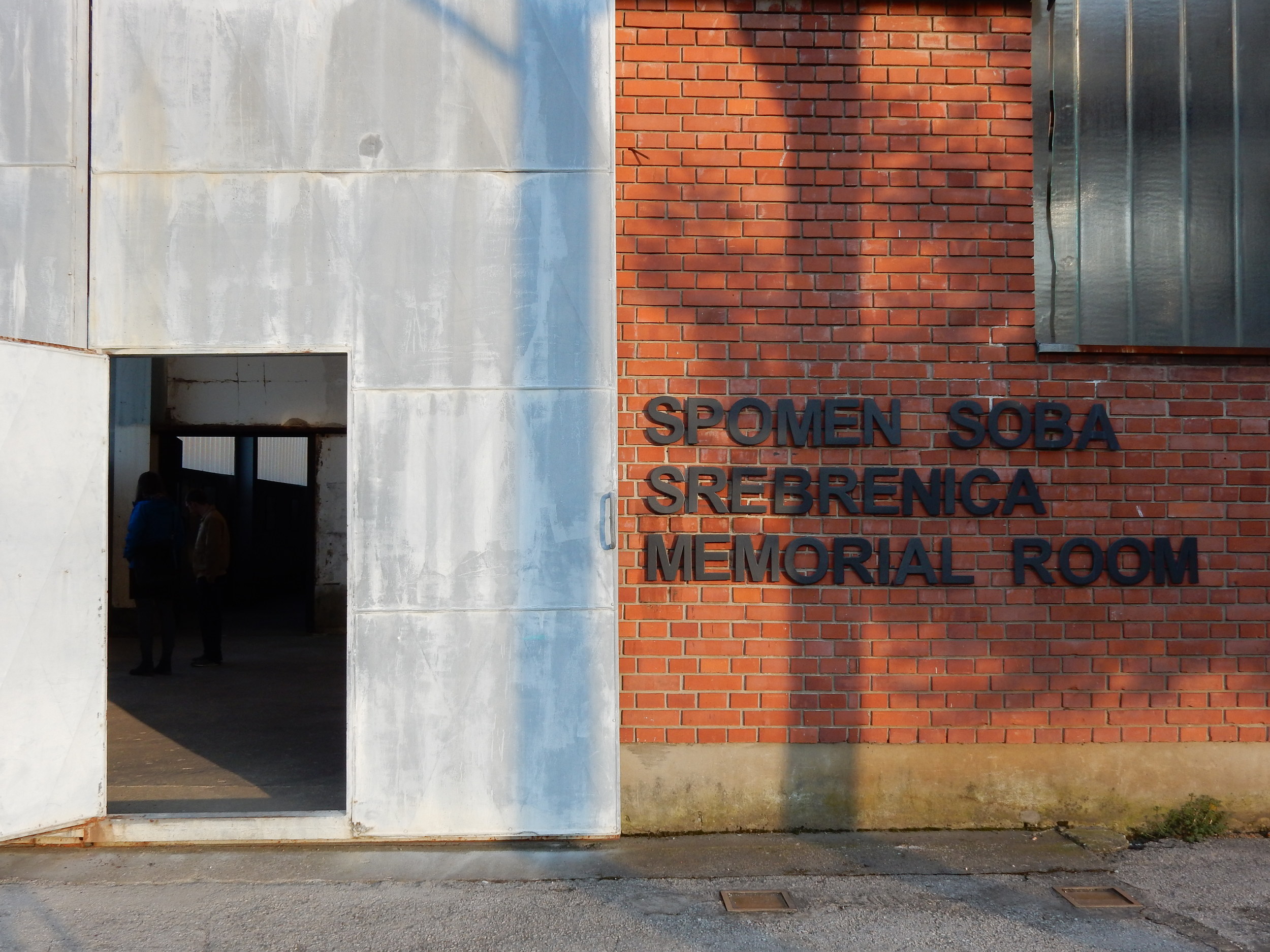

From April 20th to the 23rd, the Spring 23 Cohort traveled to Vukovar. We first visited Jasenovac memorial site, a former concentration camp during World War II. At the concentration camp, 80,000-100,000 ethnic Serbs, Jews, Roma, and political enemies of the Ustaša regime were killed. Many in very brutal ways. While visiting the museum and the concentration camp land, seeing victims' names and photos, we remember their suffering and recall that this does not define them. Each victim had a story and a life.

The next day, we visited the memorial hospital where our tour guide herself had spent time in 1991 and given birth to a baby girl. Many of the rooms are still set up in the way they were during the bombing by Serbian forces. Our tour guide showed us marks in the ceiling where bombs had fallen and operating tables used. It is easy to be stuck in the past, reliving the tragedy at the hospital. However, our tour guide pointed out the bright spots of 16 babies being born healthy and now living adults or the selfless acts of doctors and nurses who worked around the clock. We later went to the Ovčara memorial site, where those taken from the memorial hospital by Serbian paramilitary forces are remembered. Pictures of the victims light slowly on and off to help remember their life and the tragedy that has occurred but also acknowledge this has occurred in the past and there is a future. Lastly, on Tuesday, we went to the Memorial Cemetery, which marks the site of the mass graves. While remembering a dark and tragic time in Croatian history, the cemetery is peacefully covered with flowers and greenery. Experiencing the concentration camp, memorial hospital, and memorial sites, it is easy to be stuck in the past, reliving the trauma and tragedies. However, in confronting these historical traumas, we do justice to those who have suffered while recognizing the importance of acting for peace and preventing such crimes. In the evening on Tuesday, we spoke to Saša, head of Youth Peace Group Danube, a nonprofit that promotes the development of young people while mainly in Vukovar, bringing together youth of all cultures to help build a path forward. Saša's speech helped demonstrate the importance of moving forward past tragedies on both sides.

On Wednesday, we spoke to the hotel owner Pavao Josić about his goal to fight corruption. Pavao, a man of many skills, including creating an eco-friendly hotel, combats corruption in the government by providing the community with information mainly through Facebook. While perhaps seeming innocuous, his fight has exposed many and led to a more just system. We later had our internship seminar and then drove to Ilok, where there was a tour of a wine cellar and Principovac summer castle. Finally, on the last day, we took our Literature class, reflecting on tragedy but also the importance to move forward, and then drove back to Zagreb.

![Spring [Cohort 2018] is Here!](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54784e3ce4b09b5c2131e0ae/1522943350493-3ZGY5AMVV7S7H2A5S2WC/IMG_0545.jpg)